Fort Wingate Historic District, Fort Wingate, New Mexico, USA

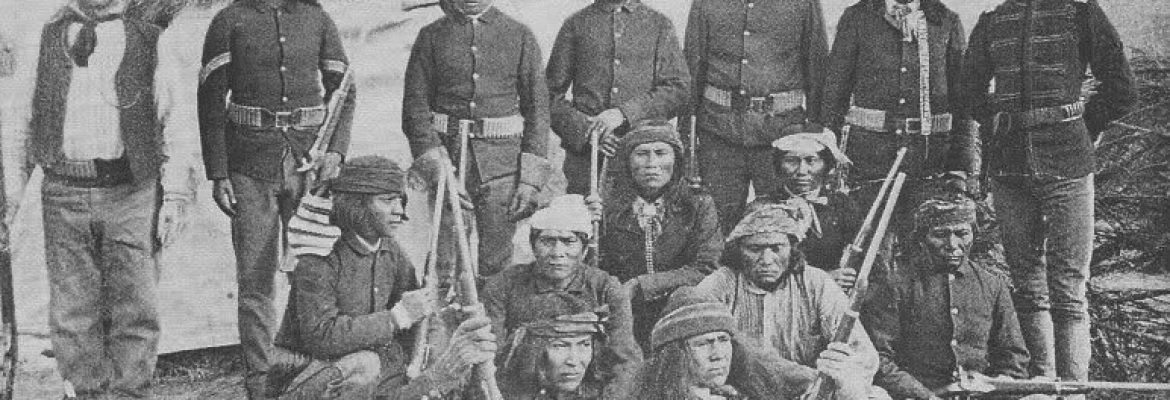

Fort Wingate is near Gallup, New Mexico. There were two locations in New Mexico that had this name. The first one was located near San Rafael. The new location called Ft. Wingate was established on the southern edge of the Navajo territory in 1868. The initial purpose of the fort was to control the large Navajo tribe to its north. It was involved with the Navajo’s Long Walk. From 1870 onward the garrison was concerned with Apaches to the south and hundreds of Navajo Scouts were enlisted at the fort through 1890.

Fort Wingate Historic District, Fort Wingate, New Mexico, USA Fort Wingate sits among the red rocks seven miles east of Gallup along Interstate 40, next to the reservations of the Navajo Nation and the Zuni Tribe. An ancestral homeland to both tribes, Fort Wingate contains more than 400 ruins traceable to both Navajo and Zuni traditions. The fort’s history is deeply rooted in the Indian wars of the late 1800s, fought between American Indian tribes and the United States military for control of what would become the western United States. Fort Wingate later became a key military installation along Route 66 during World War II.

The United States established Fort Fauntleroy on the site of modern Fort Wingate in 1860, as part of a campaign against the region’s Navajo population. The Civil War disrupted the campaign, and Fort Fauntleroy’s troops quickly deployed away from New Mexico. Fort Fauntleroy served briefly as a mail station before being abandoned c.1865.

Navajo and United States forces continued to contest the surrounding territory. General James Carleton, commander of the Department of New Mexico (a regional designation predating statehood), believed that confining the Indians to reservations was the best solution to the conflict. Joined by Ute allies, Carleton led forces against the Navajos, destroying sheep and homes and finally removing thousands of Navajos to the Bosque Redondo Reservation in a 400-mile trek called The Long Walk by the participants and their descendents. The reservation operated for four years. Poor growing conditions and lack of water on the reservation resulted in malnutrition and disease among the Navajo.

Navajo and U.S. government representatives signed a treaty in the summer of 1868 allowing the Navajo to return to their homes. The treaty also provided replacement livestock in return for the Navajo’s pledge to confine themselves to a finite area and cease raiding activities. The new Navajo reservation included a United States military installation called Fort Wingate, which occupied the site of the abandoned Fort Fauntleroy.

Fort Wingate remained a large and active installation operating primarily as a police force for the Navajo reservation and the surrounding area. One of its roles was to protect construction activities of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, which played a key role in fostering western settlement and tourism. Navajo scouts based at the fort also supported United States efforts against Apache forces to the south, and the fort became an incarceration facility for captured Apaches.

Many soldiers stationed at Fort Wingate found their conditions grim. Lieutenant John Pershing wrote to a correspondent “this post is a … and no question – tumbled down, old quarters, though Stots is repairing it as fast as he can. The winters are severe…it is always bleak and the surrounding country is barren absolutely.” An 1896 fire destroyed many of the fort’s buildings, which the military replaced with buildings of local red sandstone shortly after 1900.

The United States decommissioned the fort in 1912, making way for a variety of 20th-century uses. The fort briefly served again in 1914 and 1915 when an internment camp in a fenced enclosure just north of the post housed refugees from the Mexican Revolution. Just four years later, the United States Ordnance Department took possession of the site, using it as a depot. In 1925, the fort became the site of an Indian school.

Route 66 became an important artery for military logistics during World War II, making military sites along its way busy places and supporting economic growth in nearby communities. War heightened the demand for munitions storage facilities. Fort Wingate, with its earthen, igloo-like storage buildings visible from Route 66, became a major storage center. Most famous of Fort Wingate’s World War II contributions, however, were the Navajo code talkers who trained here. The code talkers baffled Japanese forces in the Pacific using a code based on the Navajo language.

Remaining at Fort Wingate today are several historic features. From its military period, the fort retains parade grounds, an 1883 adobe clubhouse, one barracks, and a row of c.1900 officers’ quarters. The cemetery remains, though most military burials were removed to the Santa Fe National Cemetery in 1915. The Fort Wingate cemetery continues to be used for the burial of Navajo veterans and graves of some of the Mexican refugees remain. Though the Bureau of Indian Affairs demolished many of the fort’s historic buildings in the late 1950s to build the still-active Wingate Elementary School, the first school’s barn and silos, power house, and maintenance building remain. The National Park Service listed the Fort Wingate Historic District in the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.